HMAS Australia (1911) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMAS ''Australia'' was one of three s built for the defence of the

''Australia'' had an

''Australia'' had an

''Australia'' received a fire-control director sometime between mid-1915 and May 1916; this centralised fire control under the director officer, who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy, as it was easier to spot the fall of shells and eliminated the problem of the ship's roll dispersing the shells when each turret fired independently. ''Australia'' was also fitted with an additional inch of armour around the midships turrets following the Battle of Jutland.

By 1918, ''Australia'' carried a

''Australia'' received a fire-control director sometime between mid-1915 and May 1916; this centralised fire control under the director officer, who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy, as it was easier to spot the fall of shells and eliminated the problem of the ship's roll dispersing the shells when each turret fired independently. ''Australia'' was also fitted with an additional inch of armour around the midships turrets following the Battle of Jutland.

By 1918, ''Australia'' carried a

At the start of the 20th century, the British Admiralty maintained that naval defence of the

At the start of the 20th century, the British Admiralty maintained that naval defence of the

''Australia'' was escorted by the light cruiser during the voyage to Australia. On 25 July, the two ships left England for South Africa: the visit was part of an agreement between the Prime Ministers of Australia and South Africa to promote the link between the two nations, along with the nations' links to the rest of the British Empire. The two ships were anchored in

''Australia'' was escorted by the light cruiser during the voyage to Australia. On 25 July, the two ships left England for South Africa: the visit was part of an agreement between the Prime Ministers of Australia and South Africa to promote the link between the two nations, along with the nations' links to the rest of the British Empire. The two ships were anchored in

During July 1914, ''Australia'' and other units of the RAN fleet were on a training cruise in Queensland waters.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 30 On 27 July, the

During July 1914, ''Australia'' and other units of the RAN fleet were on a training cruise in Queensland waters.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 30 On 27 July, the

The Australian invasion force had mustered off the

The Australian invasion force had mustered off the

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank, the Admiralty saw the need for dedicated battlecruiser squadrons in British waters, and earmarked ''Australia'' to lead one of them. On 11 January, while en route to Jamaica, ''Australia'' was diverted to

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank, the Admiralty saw the need for dedicated battlecruiser squadrons in British waters, and earmarked ''Australia'' to lead one of them. On 11 January, while en route to Jamaica, ''Australia'' was diverted to  On the morning of 21 April, ''Australia'' and her sister ships sailed again for the Skagerrak, this time to support efforts to disrupt the transport of Swedish ore to Germany. The planned destroyer sweep of the

On the morning of 21 April, ''Australia'' and her sister ships sailed again for the Skagerrak, this time to support efforts to disrupt the transport of Swedish ore to Germany. The planned destroyer sweep of the

After being formally farewelled by the Prince of Wales and First Sea Lord

After being formally farewelled by the Prince of Wales and First Sea Lord

Representatives of the ship's company approached Captain Claude Cumberlege to ask for a one-day delay on departure; this would allow the sailors to have a full weekend of leave, give Perth-born personnel the chance to visit their families, and give personnel another chance to invite people aboard. Cumberlege replied that as ''Australia'' had a tight schedule of "welcome home" port visits, such delays could not even be considered. The next morning, at around 10:30, between 80 and 100 sailors gathered in front of 'P' turret, some in working uniform, others who had just returned from shore leave still in libertyman rig. Cumberlege sent the executive officer to find out why the men had assembled, and on learning that they were repeating the previous day's request for a delay in departure, went down to address them. In a strict, legalistic tone, he informed the sailors that delaying ''Australia''s departure was impossible, and ordered them to disperse. The group obeyed this order, although some were vocal in their displeasure.Frame and Baker, ''Mutiny!'', p. 101 Shortly after, ''Australia'' was ready to depart, but when the order to release the mooring lines and get underway was given, Cumberlege was informed that the stokers had abandoned the boiler rooms.Frame and Baker, ''Mutiny!'', p. 102 After the assembly on deck, some sailors had masked themselves with black handkerchiefs, and encouraged or intimidated the stokers on duty into leaving their posts, leaving the navy's flagship stranded at the buoy, in full view of dignitaries and crowds lining the nearby wharf. The senior non-commissioned officers, along with sailors drafted from other departments, were sent to the boiler room to get ''Australia'' moving, and departure from Fremantle was only delayed by an hour.

Australian naval historians David Stevens and Tom Frame disagree on what happened next. Stevens states that Cumberledge assembled the ship's company in the early afternoon, read the ''

Representatives of the ship's company approached Captain Claude Cumberlege to ask for a one-day delay on departure; this would allow the sailors to have a full weekend of leave, give Perth-born personnel the chance to visit their families, and give personnel another chance to invite people aboard. Cumberlege replied that as ''Australia'' had a tight schedule of "welcome home" port visits, such delays could not even be considered. The next morning, at around 10:30, between 80 and 100 sailors gathered in front of 'P' turret, some in working uniform, others who had just returned from shore leave still in libertyman rig. Cumberlege sent the executive officer to find out why the men had assembled, and on learning that they were repeating the previous day's request for a delay in departure, went down to address them. In a strict, legalistic tone, he informed the sailors that delaying ''Australia''s departure was impossible, and ordered them to disperse. The group obeyed this order, although some were vocal in their displeasure.Frame and Baker, ''Mutiny!'', p. 101 Shortly after, ''Australia'' was ready to depart, but when the order to release the mooring lines and get underway was given, Cumberlege was informed that the stokers had abandoned the boiler rooms.Frame and Baker, ''Mutiny!'', p. 102 After the assembly on deck, some sailors had masked themselves with black handkerchiefs, and encouraged or intimidated the stokers on duty into leaving their posts, leaving the navy's flagship stranded at the buoy, in full view of dignitaries and crowds lining the nearby wharf. The senior non-commissioned officers, along with sailors drafted from other departments, were sent to the boiler room to get ''Australia'' moving, and departure from Fremantle was only delayed by an hour.

Australian naval historians David Stevens and Tom Frame disagree on what happened next. Stevens states that Cumberledge assembled the ship's company in the early afternoon, read the ''

When ''Australia'' was decommissioned in 1921, some of her equipment was removed for use in other ships, but after the November 1923 Cabinet decision confirming the scuttling, RAN personnel and private contractors began to remove piping and other small fittings.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'', p. 182 Between November 1923 and January 1924, £68,000 of equipment was reclaimed; over half was donated to tertiary education centres (some of which was still in use in the 1970s), while the rest was either marked for use in future warships, or sold as souvenirs. Some consideration was given to reusing ''Australia''s 12-inch guns in coastal fortifications, but this did not occur as ammunition for these weapons was no longer being manufactured by the British, and the cost of building suitable structures was excessive.Jones, ''A Fall From Favour'', p. 59 It was instead decided to sink the gun turrets and spare barrels with the rest of the ship. There was also a proposal to remove ''Australia''s conning tower and install it on the Sydney Harbour foreshore; although this did not go ahead, the idea was later used when the foremast of was erected as a monument at

When ''Australia'' was decommissioned in 1921, some of her equipment was removed for use in other ships, but after the November 1923 Cabinet decision confirming the scuttling, RAN personnel and private contractors began to remove piping and other small fittings.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'', p. 182 Between November 1923 and January 1924, £68,000 of equipment was reclaimed; over half was donated to tertiary education centres (some of which was still in use in the 1970s), while the rest was either marked for use in future warships, or sold as souvenirs. Some consideration was given to reusing ''Australia''s 12-inch guns in coastal fortifications, but this did not occur as ammunition for these weapons was no longer being manufactured by the British, and the cost of building suitable structures was excessive.Jones, ''A Fall From Favour'', p. 59 It was instead decided to sink the gun turrets and spare barrels with the rest of the ship. There was also a proposal to remove ''Australia''s conning tower and install it on the Sydney Harbour foreshore; although this did not go ahead, the idea was later used when the foremast of was erected as a monument at  The scuttling was originally scheduled for Anzac Day (25 April) 1924, but was brought forward to 12 April, so the visiting British Special Service Squadron could participate. On the day of the sinking, ''Australia'' was towed out to a point north east of Sydney Heads.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 38 Under the terms of the Washington Treaty, the battlecruiser needed to be sunk in water that was deep enough to make it infeasible to refloat her at a future date. The former flagship was escorted by the Australian warships ''Melbourne'', ''Brisbane'', ''Adelaide'', ''Anzac'', and ''Stalwart'', the ships of the Special Service Squadron, and several civilian ferries carrying passengers.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 17 Many personnel volunteered to be part of the scuttling party, but only those who had served aboard her were selected. At 14:30, the scuttling party set the charges, opened all

The scuttling was originally scheduled for Anzac Day (25 April) 1924, but was brought forward to 12 April, so the visiting British Special Service Squadron could participate. On the day of the sinking, ''Australia'' was towed out to a point north east of Sydney Heads.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 38 Under the terms of the Washington Treaty, the battlecruiser needed to be sunk in water that was deep enough to make it infeasible to refloat her at a future date. The former flagship was escorted by the Australian warships ''Melbourne'', ''Brisbane'', ''Adelaide'', ''Anzac'', and ''Stalwart'', the ships of the Special Service Squadron, and several civilian ferries carrying passengers.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 17 Many personnel volunteered to be part of the scuttling party, but only those who had served aboard her were selected. At 14:30, the scuttling party set the charges, opened all  There are two schools of thought surrounding the decision to scuttle the battlecruiser. The first is that sinking ''Australia'' was a major blow to the nation's ability to defend herself. Following the battlecruiser's scuttling, the most powerful warships in the RAN were four old light cruisers. The battlecruiser had served as a deterrent to German naval action against Australia during the war, and with growing tensions between Japan and the United States of America, that deterrence might have been required if the nations had become openly hostile towards each other or towards Australia.Kerr, ''A Loss More Symbolic Than Material?'', in ''Semaphore'', pp. 1–2 The opposing argument is that, while an emotive and symbolic loss, the ship was obsolete, and would have been a drain on resources. Operating and maintaining the warship was beyond the capabilities of the RAN's post-war budgets, necessitating the ship's reduction in status in 1920 and assignment to reserve in 1921.''A Loss More Symbolic Than Material?'', in ''Semaphore'', p. 2 Ammunition and replacement barrels for the main guns were no longer manufactured. To remain effective, ''Australia'' required major modernisation (including new propulsion machinery, increased armour and armament, and new fire control systems) at a cost equivalent to a new .

In 1990, a large, unknown shipwreck was encountered by the Fugro Seafloor Surveys vessel MV ''Moana Wave 1'' while surveying the path of the

There are two schools of thought surrounding the decision to scuttle the battlecruiser. The first is that sinking ''Australia'' was a major blow to the nation's ability to defend herself. Following the battlecruiser's scuttling, the most powerful warships in the RAN were four old light cruisers. The battlecruiser had served as a deterrent to German naval action against Australia during the war, and with growing tensions between Japan and the United States of America, that deterrence might have been required if the nations had become openly hostile towards each other or towards Australia.Kerr, ''A Loss More Symbolic Than Material?'', in ''Semaphore'', pp. 1–2 The opposing argument is that, while an emotive and symbolic loss, the ship was obsolete, and would have been a drain on resources. Operating and maintaining the warship was beyond the capabilities of the RAN's post-war budgets, necessitating the ship's reduction in status in 1920 and assignment to reserve in 1921.''A Loss More Symbolic Than Material?'', in ''Semaphore'', p. 2 Ammunition and replacement barrels for the main guns were no longer manufactured. To remain effective, ''Australia'' required major modernisation (including new propulsion machinery, increased armour and armament, and new fire control systems) at a cost equivalent to a new .

In 1990, a large, unknown shipwreck was encountered by the Fugro Seafloor Surveys vessel MV ''Moana Wave 1'' while surveying the path of the

Thus Britain Honours Her Word

– A

HMAS Australia (I)

– The Royal Australian Navy webpage for ''Australia''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Australia (1911) 1911 ships Ships built on the River Clyde Scuttled vessels of New South Wales World War I battlecruisers of Australia Indefatigable-class battlecruisers of the Royal Australian Navy Maritime incidents in 1924

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

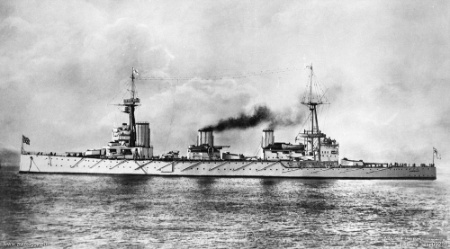

. Ordered by the Australian government in 1909, she was launched in 1911, and commissioned as flagship of the fledgling Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

(RAN) in 1913. ''Australia'' was the only capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

ever to serve in the RAN.

At the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, ''Australia'' was tasked with finding and destroying the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

, which was prompted to withdraw from the Pacific by the battlecruiser's presence. Repeated diversions to support the capture of German colonies

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

and Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, as well as an overcautious Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, prevented the battlecruiser from engaging the German squadron before the latter's destruction. ''Australia'' was then assigned to North Sea operations, which consisted primarily of patrols and exercises, until the end of the war. During this time, ''Australia'' was involved in early attempts at naval aviation

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based ...

, and 11 of her personnel participated in the Zeebrugge Raid

The Zeebrugge Raid ( nl, Aanval op de haven van Zeebrugge;

) on 23 April 1918, was an attempt by the Royal Navy to block the Belgian port of Bruges-Zeebrugge. The British intended to sink obsolete ships in the canal entrance, to prevent Germ ...

. The battlecruiser was not at the Battle of Jutland, as she was undergoing repairs following a collision with sister ship . ''Australia'' only ever fired in anger twice: at a German merchant vessel in January 1915, and at a suspected submarine contact in December 1917.

On her return to Australian waters, several sailors aboard the warship mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

after a request for an extra day's leave

Leave may refer to:

* Permission (disambiguation)

** Permitted absence from work

*** Leave of absence, a period of time that one is to be away from one's primary job while maintaining the status of employee

*** Annual leave, allowance of time away ...

in Fremantle was denied, although other issues played a part in the mutiny, including minimal leave during the war, problems with pay, and the perception that Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

personnel were more likely to receive promotions than Australian sailors. Post-war budget cuts saw ''Australia''s role downgraded to a training ship before she was placed in reserve in 1921. The disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such as ...

provisions of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

required the destruction of ''Australia'' as part of the British Empire's commitment, and she was scuttled off Sydney Heads in 1924.

Design

The ''Indefatigable'' class of battlecruisers were based heavily on the preceding . The main difference was that the ''Indefatigable''s design was enlarged to give the ships' two-wing turrets a wider arc of fire. As a result, the ''Indefatigable'' class was not a significant improvement on the ''Invincible'' design; the ships were smaller and not as well protected as the contemporary German battlecruiser and subsequent German designs. While ''Von der Tann''s characteristics were not known when thelead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of the class, , was laid down in February 1909, the Royal Navy obtained accurate information on the German ship before work began on ''Australia'' and her sister ship .

''Australia'' had an

''Australia'' had an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of , and a maximum draught of .Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', pp. 16–17 The ship displaced at load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. She had a crew of 818 officers and ratings in 1913.Burt, ''British Battleships of World War One'', p. 91

The ship was powered by two Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

' sets of direct-drive

A direct-drive mechanism is a mechanism design where the force or torque from a prime mover is transmitted directly to the effector device (such as the drive wheels of a vehicle) without involving any intermediate couplings such as a gear train o ...

steam turbines, each driving two propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

s, using steam provided by 31 coal-burning Babcock & Wilcox boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s. The turbines were rated at and were intended to give the ship a maximum speed of . However, during trials in 1913, ''Australia'' turbines provided , allowing her to reach . ''Australia'' carried enough coal and fuel oil to give her a range of at a cruising speed of .

''Australia'' carried eight BL Mark X guns in four BVIII* twin turrets; the largest guns fitted to any Australian warship. Two turrets were mounted fore and aft on the centreline, identified as 'A' and 'X' respectively. The other two were wing turrets mounted amidships and staggered diagonally: 'P' was forward and to port of the centre funnel, while 'Q' was situated starboard and aft. Each wing turret had some limited ability to fire to the opposite side. Her secondary armament consisted of sixteen BL Mark VII guns positioned in the superstructure. She mounted two submerged tubes

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* ''The Tube'' (TV series), a music related TV series by Channel 4 in the United Kingdom

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a ...

for 18-inch torpedoes, one on each side aft of 'X' barbette, and 12 torpedoes were carried.Campbell, ''Battle Cruisers'', p. 14

The ''Indefatigable''s were protected by a waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

armoured belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating t ...

that extended between and covered the end barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s. Their armoured deck ranged in thickness between with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

turret faces were thick, and the turrets were supported by barbettes of the same thickness.

''Australia''s 'A' turret was fitted with a rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

at the rear of the turret roof. It was also equipped to control the entire main armament, in case normal fire control positions were knocked out or rendered inoperable.

Modifications

''Australia'' received a single QF 20 cwt anti-aircraft (AA) gun on a high-angle Mark II mount that was added in March 1915. This had a maximum depression of 10° and a maximum elevation of 90°. It fired a shell at a muzzle velocity of at a rate of fire of 12–14 rounds per minute. It had a maximum effective ceiling of . It was provided with 500 rounds. The 4-inch guns were enclosed in casemates and given blast shields during a refit in November 1915 to better protect the gun crews from weather and enemy action, and two aft guns were removed at the same time.Campbell, ''Battle Cruisers'', p. 13 An additional 4-inch gun was fitted during 1917 as an AA gun. It was mounted on a Mark II high-angle mounting with a maximum elevation of 60°. It had a reduced propellant charge with a muzzle velocity of only ;''British 4"/50 (10.2 cm) BL Mark VII'', Navweapons.com 100 rounds were carried for it. ''Australia'' received a fire-control director sometime between mid-1915 and May 1916; this centralised fire control under the director officer, who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy, as it was easier to spot the fall of shells and eliminated the problem of the ship's roll dispersing the shells when each turret fired independently. ''Australia'' was also fitted with an additional inch of armour around the midships turrets following the Battle of Jutland.

By 1918, ''Australia'' carried a

''Australia'' received a fire-control director sometime between mid-1915 and May 1916; this centralised fire control under the director officer, who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy, as it was easier to spot the fall of shells and eliminated the problem of the ship's roll dispersing the shells when each turret fired independently. ''Australia'' was also fitted with an additional inch of armour around the midships turrets following the Battle of Jutland.

By 1918, ''Australia'' carried a Sopwith Pup

The Sopwith Pup is a British single-seater biplane fighter aircraft built by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It entered service with the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps in the autumn of 1916. With pleasant flying character ...

and a Sopwith 1½ Strutter on platforms fitted to the top of 'P' and 'Q' turrets. The first flying off by a 1½ Strutter was from ''Australia''s 'Q' turret on 4 April 1918. Each platform had a canvas hangar to protect the aircraft during inclement weather. At the end of World War I, ''Australia'' was described as "the least obsolescent of her class".Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 284

After the war, both anti-aircraft guns were replaced by a pair of QF 4-inch Mark V guns on manually operated high-angle mounts in January 1920. Their elevation limits were −5° to 80°. The guns fired a shell at a muzzle velocity of at a rate of fire of 10–15 rounds per minute. They had a maximum effective ceiling of .

Acquisition and construction

At the start of the 20th century, the British Admiralty maintained that naval defence of the

At the start of the 20th century, the British Admiralty maintained that naval defence of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, including the Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s, should be unified under the Royal Navy. Attitudes on this matter softened during the first decade, and at the 1909 Imperial Conference, the Admiralty proposed the creation of 'Fleet Units': forces consisting of a battlecruiser, three light cruisers, six destroyers, and three submarines.Lambert, in Nielson & Kennedy, ''Far Flung Lines'', p. 64 Although some were to be operated by the Royal Navy at distant bases, particularly in the Far East, the Dominions were encouraged to purchase fleet units to serve as the core of new national navies: Australia and Canada were both encouraged to do so at earliest opportunity, New Zealand was asked to partially subsidise a fleet unit for the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 18 ...

, and there were plans for South Africa to fund one at a future point. Each fleet unit was designed as a "navy in miniature", and would operate under the control of the purchasing Dominion during peacetime. In the event of widespread conflict, the fleet units would come under Admiralty control, and would be merged to form larger fleets for regional defence. Australia was the only Dominion to purchase a full fleet unit, and while the New Zealand-funded battlecruiser was donated to the Royal Navy outright, no other nation purchased ships under the fleet unit plan.

On 9 December 1909, a cable was sent by Governor-General Lord Dudley to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, The Earl of Crewe, requesting that construction of three cruisers and an ''Indefatigable''-class battlecruiser start at earliest opportunity.Frame, ''No Pleasure Cruise'', p. 92 It is unclear why this design was selected, given that it was known to be inferior to the battlecruisers entering service with the German Imperial Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

(''Kaiserliche Marine''). Historian John Roberts has suggested that the request may have been attributable to the Royal Navy's practice of using small battleships and large cruisers as flagships of stations far from Britain, or it might have reflected the preferences of the First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

and Admiral of the Fleet John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic bishop, cardinal, and theologian. Fisher was also an academic and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Fisher was executed by o ...

, preferences not widely shared.

The Australian Government decided on the name ''Australia'', as this would avoid claims of favouritism or association with a particular state.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'', p. 172 The ship's badge

Naval heraldry is a form of identification used by naval vessels from the end of the 19th century onwards, after distinguishing features such as Figurehead (object), figureheads and gilding were discouraged or banned by several navies.

Naval heral ...

depicted the Federation Star overlaid by a naval crown, and her motto was "Endeavour", reflecting both an idealisation of Australians' national spirit and attitude, and a connection to James Cook and HM Bark ''Endeavour''. On 6 May 1910, George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales fr ...

, Australia's high commissioner to the United Kingdom

The following is the list of ambassadors and high commissioners to the United Kingdom, or more formally, to the Court of St James's. High commissioners represent member states of the Commonwealth of Nations and ambassadors represent other sta ...

, sent a telegram cable to the Australian Government suggesting that the ship be named after the newly crowned King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, but this was rebuffed.

Bids for construction were forwarded to the Australian Government by Reid on 7 March 1910, and Prime Minister Alfred Deakin approved the submission by John Brown & Company

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including , , , , , and the ''Queen Elizabeth 2''.

At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of ...

to construct the hull and machinery, with separate contracts awarded to Armstrong Armstrong may refer to:

Places

* Armstrong Creek (disambiguation), various places

Antarctica

* Armstrong Reef, Biscoe Islands

Argentina

* Armstrong, Santa Fe

Australia

* Armstrong, Victoria

Canada

* Armstrong, British Columbia

* Armstrong ...

and Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public i ...

for the battlecruiser's armament.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'', p. 171 The total cost of construction was set at £2 million. Contracts were signed between the Admiralty and the builders to avoid the problems of distant supervision by the Australian Government, and a close watch on proceedings was maintained by Reid and Captain Francis Haworth-Booth, the Australian Naval Representative in London.

''Australia''s keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid at John Brown & Company's Clydebank yard on 23 June 1910, and was assigned the yard number 402.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 34 The ship was launched by Lady Reid on 25 October 1911, in a ceremony which received extensive media coverage. ''Australia''s design was altered during construction to incorporate improvements in technology, including the newly developed nickel-steel armour plate. While it was intended that the entire ship be fitted with the new armour, manufacturing problems meant that older armour had to be used in some sections: the delay in sourcing the older armour plates set construction back half a year. Despite this, John Brown & Company delivered the ship £295,000 under budget.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'', p. 173

During construction, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

attempted to arrange for ''Australia'' to remain in British waters on completion.Dennis et al., ''The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History'', p. 299 Although the claim was made on strategic grounds, the reasoning behind it was so the Australian-funded ship could replace one to be purchased with British defence funds. This plan was successfully resisted by Admiral George King-Hall, then Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy's Australia Squadron The Australian Squadron was the name given to the British naval force assigned to the Australia Station from 1859 to 1911.Dennis et al. 2008, p. 67.

The Squadron was initially a small force of Royal Navy warships based in Sydney, and although inten ...

.

''Australia'' sailed for Devonport, Devon

Devonport ( ), formerly named Plymouth Dock or just Dock, is a district of Plymouth in the English county of Devon, although it was, at one time, the more important settlement. It became a county borough in 1889. Devonport was originally one o ...

in mid-February 1913 to begin her acceptance trials. Testing of the guns, torpedoes, and machinery was successful, but it was discovered that two hull plates had been damaged during the launch, requiring the battlecruiser to dock for repairs. ''Australia'' was commissioned into the RAN at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

on 21 June 1913. Two days later, Rear Admiral George Patey, the first Rear Admiral Commanding Australian Fleet, raised his flag aboard ''Australia''.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 24

At launch, the standard ship's company was 820, over half of which were Royal Navy personnel; the other half was made up of Australian-born RAN personnel, or Britons transferring from the Royal Navy to the RAN.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 25 Accommodation areas were crowded, with each man having only of space to sling his hammock when ''Australia'' was fully manned. Moreover, the ventilation system was designed for conditions in Europe, and was inadequate for the climate in and around Australia.Frame and Baker, ''Mutiny!'', p. 68 On delivery, ''Australia'' was the largest warship in the Southern Hemisphere.Frame, ''No Pleasure Cruise'', p. 97

Operational history

Voyage to Australia

Following her commissioning, ''Australia'' hosted several official events. On 30 June,King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

and Edward, Prince of Wales, visited ''Australia'' to farewell the ship.Rüger, ''Nation, Empire and Navy'', p. 179 During this visit, King George knighted Patey on the ship's quarterdeck—the first time a naval officer was knighted aboard a warship since Francis Drake.Rüger, ''Nation, Empire and Navy'', p. 180 On 1 July, Patey hosted a luncheon which was attended by imperial dignitaries, including Reid, the Agents-General of the Australian states, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, Secretary of State for the Colonies Lewis Harcourt

Lewis Vernon Harcourt, 1st Viscount Harcourt (born Reginald Vernon Harcourt; 31 January 1863 – 24 February 1922), was a British Liberal Party politician who held the Cabinet post of Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1910 to 1915. Lord ...

, and the High Commissioners of other British Dominions.Stevens, in Stevens & Reeve, ''The Navy and the Nation'' p. 174 That afternoon, 600 Australian expatriates were invited to a ceremonial farewelling, and were entertained by shows and fireworks. Journalists and cinematographers were allowed aboard to report on ''Australia'' prior to her departure, and an official reporter was embarked for the voyage to Australia: his role was to promote the ship as a symbol of the bond between Australia and the United Kingdom.

''Australia'' was escorted by the light cruiser during the voyage to Australia. On 25 July, the two ships left England for South Africa: the visit was part of an agreement between the Prime Ministers of Australia and South Africa to promote the link between the two nations, along with the nations' links to the rest of the British Empire. The two ships were anchored in

''Australia'' was escorted by the light cruiser during the voyage to Australia. On 25 July, the two ships left England for South Africa: the visit was part of an agreement between the Prime Ministers of Australia and South Africa to promote the link between the two nations, along with the nations' links to the rest of the British Empire. The two ships were anchored in Table Bay

Table Bay (Afrikaans: ''Tafelbaai'') is a natural bay on the Atlantic Ocean overlooked by Cape Town (founded 1652 by Van Riebeeck) and is at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, which stretches south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was named b ...

from 18 to 26 August, during which the ships' companies participated in parades and receptions, while tens of thousands of people came to observe the ships.Rüger, ''Nation, Empire and Navy'', p. 181 The two ships also visited Simon's Town

Simon's Town ( af, Simonstad), sometimes spelled Simonstown, is a town in the Western Cape, South Africa and is home to Naval Base Simon's Town, the South African Navy's largest base. It is located on the shores of False Bay, on the eastern ...

, while ''Australia'' additionally called into Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

. No other major ports were visited on the voyage, and the warships were instructed to avoid all major Australian ports.

''Australia'' and ''Sydney'' reached Jervis Bay

Jervis Bay () is a oceanic bay and village on the south coast of New South Wales, Australia, said to possess the whitest sand in the world.

A area of land around the southern headland of the bay is a territory of the Commonwealth of Australia ...

on 2 October, where they rendezvoused with the rest of the RAN fleet (the cruisers and , and the destroyers , , and ). The seven warships prepared for a formal fleet entry into Sydney Harbour. On 4 October, ''Australia'' led the fleet into Sydney Harbour, where responsibility for Australian naval defence was passed from the Royal Navy's Australia Squadron, commanded by King-Hall aboard HMS ''Cambrian'', to the RAN, commanded by Patey aboard ''Australia''.

Early service

In her first year of service, ''Australia'' visited as many major Australian ports as possible, to expose the new navy to the widest possible audience and induce feelings of nationhood: naval historian David Stevens claims that these visits did more to break down state rivalries and promote the unity of Australia as a federated commonwealth than any other event. During late 1913, footage for the film ''Sea Dogs of Australia

''Sea Dogs of Australia'' is a 1913 Australian silent film about an Australian naval officer blackmailed into helping a foreign spy. The film was publicly released in August 1914, but was almost immediately withdrawn after the Minister for Defenc ...

'' was filmed aboard the battlecruiser; the film was withdrawn almost immediately after first screening in August 1914 because of security concerns.

During July 1914, ''Australia'' and other units of the RAN fleet were on a training cruise in Queensland waters.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 30 On 27 July, the

During July 1914, ''Australia'' and other units of the RAN fleet were on a training cruise in Queensland waters.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 30 On 27 July, the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board

The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board was the governing authority over the Royal Australian Navy from its inception and through World Wars I and II. The board was established on 1 March 1911 and consisted of civilian members of the Australian ...

learnt through press telegrams that the British Admiralty thought that there would be imminent and widespread war in Europe following the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Pri ...

, and had begun to position its fleets as a precaution. Three days later, the Board learnt that the official warning telegram had been sent: at 22:30, ''Australia'' was recalled to Sydney to take on coal and stores.

On 3 August, the RAN was placed under Admiralty control. Orders for RAN warships were prepared over the next few days: ''Australia'' was assigned to the concentration of British naval power on the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 18 ...

, but was allowed to seek out and destroy any armoured warships (particularly those of the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

) in the Australian Station before doing so.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 32 Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy in ...

, commander of the German squadron, was aware of ''Australia''s presence in the region and her superiority to his entire force; the German admiral's plan was to harass British shipping and colonies in the Pacific until the presence of ''Australia'' and the China Squadron forced his fleet to relocate to other seas.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 33

World War I

Securing local waters

The British Empire declared war on Germany on 5 August, and the RAN swung into action. ''Australia'' had departed Sydney the night before, and was heading north to rendezvous with other RAN vessels south ofGerman New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

. The German colonial capital of Rabaul was considered a likely base of operations for von Spee, and Patey put together a plan to clear the harbour. ''Australia''s role was to hang back: if the armoured cruisers and were present, the other RAN vessels would lure them into range of the battlecruiser. The night-time operation was executed on 11 August, and no German ships were found in the harbour. Over the next two days, ''Australia'' and the other ships unsuccessfully searched the nearby bays and coastline for the German ships and any wireless stations, before returning to Port Moresby to refuel.

In late August, ''Australia'' and escorted a New Zealand occupation force to German Samoa

German Samoa (german: Deutsch-Samoa) was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1920, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the independent state of Samoa, formerly ''Western Samoa''. Samoa was the las ...

.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 35 Patey believed that the German fleet was likely to be in the eastern Pacific, and Samoa would be a logical move. Providing protection for the New Zealand troopships was a beneficial coincidence, although the timing could have been better, as an Australian expedition to occupy German New Guinea departed from Sydney a few days after the New Zealand force left home waters—''Australia'' was expected to support both, but Patey only learned of the expeditions after they had commenced their journeys. The battlecruiser left Port Moresby on 17 August and was met by ''Melbourne'' en route on 20 August. The next day, they reached Nouméa and the New Zealand occupation force, consisting of the troopships ''Moeraki'' and ''Monowai'', the French cruiser , and three s.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 59 The grounding of ''Monowai'' delayed the expedition's departure until 23 August; the ships reached Suva, Fiji on 26 August, and arrived off Apia

Apia () is the capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

...

early in the morning of 30 August. The city surrendered without a fight, freeing ''Australia'' and ''Melbourne'' to depart at noon on 31 August to meet the Australian force bound for Rabaul.

The Australian invasion force had mustered off the

The Australian invasion force had mustered off the Louisiade Archipelago

The Louisiade Archipelago is a string of ten larger volcanic islands frequently fringed by coral reefs, and 90 smaller coral islands in Papua New Guinea.

It is located 200 km southeast of New Guinea, stretching over more than and spread ...

by 9 September; the assembled ships included ''Australia'', the cruisers , and , the destroyers , , and , the submarines and , the auxiliary cruiser , the storeship , three colliers and an oiler. The force sailed north, and at 06:00 on 11 September, ''Australia'' deployed two picket boat

A picket boat is a type of small naval craft. These are used for harbor patrol and other close inshore work, and have often been carried by larger warships as a ship's boat. They range in size between 30 and 55 feet.

Patrol boats, or any craft en ...

s to secure Karavia Bay

Karavia Bay is a bay near Rabaul, New Britain, Papua New Guinea. Simpson Harbour is located to the north, while to the east is Blanche Bay.Rottman, p.172.

The naval battle of Karavia Bay was fought in February 1944 during World War II

...

for the expeditionary force's transports and supply ships. Later that day, ''Australia'' captured the German steamer ''Sumatra'' off Cape Tawui. After this, the battlecruiser stood off, in case she was required to shell one of the two wireless stations the occupation force was attempting to capture. The German colony was captured, and on 15 September, ''Australia'' departed for Sydney.

Pursuit of von Spee

The presence of ''Australia'' around the former German colonies, combined with the likelihood of Japan declaring war on Germany, prompted von Spee to withdraw his ships from the region. On 13 August, the East Asia Squadron—except for , which was sent to prey on British shipping in the Indian Ocean—had begun to move eastwards.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 29 After appearing off Samoa on 14 September, then attacking Tahiti eight days later, von Spee led his force to South America, and from there planned to sail for the Atlantic.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 36 Patey was ordered on 17 September to head back north with ''Australia'' and ''Sydney'' to protect the Australian expeditionary force. On 1 October, ''Australia'', ''Sydney'', ''Montcalm'', and ''Encounter'' headed north from Rabaul to find the German ships, but turned around to return at midnight, after receiving an Admiralty message about the Tahiti attack.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', pp. 103–104 Although Patey suspected that the Germans were heading for South America and wanted to follow with ''Australia'', the Admiralty was unsure that the intelligence was accurate, and tasked the battlecruiser with patrolling around Fiji in case they returned. ''Australia'' reached Suva on 12 October, and spent the next four weeks patrolling the waters around Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia: despite Patey's desires to range out further, Admiralty orders kept him chained to Suva until early November. As Patey predicted, von Spee had continued east, and it was not until his force inflicted the first defeat on the Royal Navy in 100 years at theBattle of Coronel

The Battle of Coronel was a First World War Imperial German Navy victory over the Royal Navy on 1 November 1914, off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. The East Asia Squadron (''Ostasiengeschwader'' or ''Kreuzergeschwader'') ...

that ''Australia'' was allowed to pursue. Departing on 8 November, the battlecruiser replenished coal from a pre-positioned collier on 14 November, and reached Chamela Bay (near Manzanillo, Mexico

Manzanillo () is a city and seat of Manzanillo Municipality, in the Mexican state of Colima. The city, located on the Pacific Ocean, contains Mexico's busiest port, responsible for handling Pacific cargo for the Mexico City area. It is the large ...

) 12 days later.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 125 Patey was made commander of a multinational squadron tasked with preventing the German squadron from sailing north to Canadian waters, or following them if they attempted to enter the Atlantic via the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

or around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

. Patey's ships included ''Australia'', the British light cruiser and the Japanese cruisers , , and the ex-Russian battleship ''Hizen''. The ships made for the Galapagos Islands, which were searched from 4 to 6 December.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 126 After finding no trace of von Spee's force, the Admiralty ordered Patey to investigate the South American coast from Perlas Island down to the Gulf of Guayaquil

The Gulf of Guayaquil is a large body of water of the Pacific Ocean in western South America. Its northern limit is the city of Santa Elena, in Ecuador, and its southern limit is Cabo Blanco, in Peru.

The gulf takes its name from the city of Gua ...

. The German squadron had sailed for the Atlantic via Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, and was defeated by a British fleet after attempting to raid the Falkland Islands on 8 December.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 37 Patey's squadron learned of this 10 December, while off the Gulf of Panama

The Gulf of Panama ( es, Golfo de Panamá) is a gulf of the Pacific Ocean off the southern coast of Panama, where most of eastern Panama's southern shores adjoin it. The Gulf has a maximum width of , a maximum depth of and the size of . The Pana ...

; ''Australia''s personnel were disappointed that they did not have the chance to take on ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau''. Nevertheless, the battlecruiser's presence in the Pacific during 1914 had provided an important counter to the German armoured cruisers, and enabled the RAN to participate in the Admiralty's global strategy. Moreover, it is unlikely that the attack on Rabaul would have gone ahead had ''Australia'' not been available to protect the landing force.Jones, ''A Fall From Favour'', p. 57

North Sea operations

As the threat of a German naval attack had been removed by the destruction of the East Asia Squadron, ''Australia'' was free for deployment elsewhere.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 127 Initially, the battlecruiser was to serve as flagship of the West Indies Squadron, with the task of pursuing and destroying any German vessels that evadedNorth Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

blockades.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 262 ''Australia'' was ordered to sail to Jamaica via the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, but as it was closed to heavy shipping, she was forced to sail down the coast of South America and pass through the Strait of Magellan during 31 December 1914 and 1 January 1915—''Australia'' is the only ship of the RAN to cross from the Pacific to the Atlantic by sailing under South America. During the crossing, one of the warship's propellers was damaged, and she had to limp to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

at half speed.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 128 Temporary repairs were made, and ''Australia'' departed on 5 January. A vessel well clear of the usual shipping routes was spotted on the afternoon of the next day, and the battlecruiser attempted to pursue, but was hampered by the damaged propeller. Unable to close the gap before sunset, a warning shot was fired from 'A' turret, which caused the ship—the former German passenger liner, now naval auxiliary ''Eleonora Woermann''—to stop and be captured. As ''Australia'' could not spare enough personnel to secure and operate the merchant ship, and ''Eleonora Woermann'' was too slow to keep pace with the battlecruiser, the German crew were taken aboard and the ship was sunk.

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank, the Admiralty saw the need for dedicated battlecruiser squadrons in British waters, and earmarked ''Australia'' to lead one of them. On 11 January, while en route to Jamaica, ''Australia'' was diverted to

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank, the Admiralty saw the need for dedicated battlecruiser squadrons in British waters, and earmarked ''Australia'' to lead one of them. On 11 January, while en route to Jamaica, ''Australia'' was diverted to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Reaching there on 20 January, the battlecruiser was ordered to proceed to Plymouth, where she arrived on 28 January and paid off for a short refit. The docking was completed on 12 February, and ''Australia'' reached Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

on 17 February after sailing through a gale. She was made flagship of the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron (2nd BCS) of the Battlecruiser Fleet, part of the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

, on 22 February. Vice Admiral Patey was appointed to command this squadron. In early March, to avoid a conflict of seniority between Patey and the leader of the Battlecruiser Fleet, Vice Admiral David Beatty, Patey was reassigned to the West Indies, and Rear Admiral William Pakenham raised his flag aboard ''Australia''. British and Allied ships deployed to the North Sea were tasked with protecting the British Isles from German naval attack, and keeping the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

penned in European waters through a distant blockade while trying to lure them into a decisive battle. During her time with the 2nd BCS, ''Australia''s operations primarily consisted of training exercises (either in isolation or with other ships), patrols of the North Sea area in response to actual or perceived German movements, and some escort work.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 264 These duties were so monotonous, one sailor was driven insane.

''Australia'' joined the Grand Fleet in a sortie on 29 March, in response to intelligence that the German fleet was leaving port as the precursor to a major operation.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 269 By the next night, the German ships had withdrawn, and ''Australia'' returned to Rosyth. On 11 April, the British fleet was again deployed on the intelligence that a German force was planning an operation.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 270 The Germans intended to lay mines at the Swarte Bank, but after a scouting Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

located a British light cruiser squadron, they began to prepare for what they thought was a British attack. Heavy fog and the need to refuel caused ''Australia'' and the British vessels to return to port on 17 August, and although they were redeployed that night, they were unable to stop two German light cruisers from laying the minefield. From 26 to 28 January 1916, the 2nd BCS was positioned off the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

T ...

while the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron

The 1st Light Cruiser Squadron was a naval unit of the Royal Navy from 1913 to 1924.

History

The 1st Light Cruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy unit of the Grand Fleet during World War I. Four of its ships ('' Inconstant'', '' Galatea'', '' Cordeli ...

swept the strait in an unsuccessful search of a possible minelayer.

On the morning of 21 April, ''Australia'' and her sister ships sailed again for the Skagerrak, this time to support efforts to disrupt the transport of Swedish ore to Germany. The planned destroyer sweep of the

On the morning of 21 April, ''Australia'' and her sister ships sailed again for the Skagerrak, this time to support efforts to disrupt the transport of Swedish ore to Germany. The planned destroyer sweep of the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

was cancelled when word came that the High Seas Fleet was mobilising for an operation of their own (later learned to be timed to coincide with the Irish Easter Rising), and the British ships were ordered to a rendezvous point in the middle of the North Sea, while the rest of the Grand Fleet made for the south-eastern end of the Long Forties

200px, right

Long Forties is a zone of the northern North Sea that is fairly consistently deep.

Extent

Long Forties are between the northeast coasts of Scotland and the southwest coast of Norway, centred about 57°N 0°30′E; compare to th ...

. On the afternoon of 22 April, the Battlecruiser Fleet was patrolling to the north-west of Horn Reefs when heavy fog came down.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 274 The ships were zigzagging to avoid submarine attack, which, combined with the weather conditions, caused ''Australia'' to collide with sister ship twice in three minutes. Procedural errors were found to be the cause of the collisions, which saw ''Australia'' (the more heavily damaged of the two ships) docked for six weeks of repairs between April and June 1916.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 38 Initial inspections of the damage were made in a floating dock on the River Tyne, but the nature of the damage required a diversion to Devonport, Devon

Devonport ( ), formerly named Plymouth Dock or just Dock, is a district of Plymouth in the English county of Devon, although it was, at one time, the more important settlement. It became a county borough in 1889. Devonport was originally one o ...

for the actual repair work. The repairs were completed more quickly than expected, and ''Australia'' rejoined the 2nd BCS Squadron at Rosyth on 9 June, having missed the Battle of Jutland.

On the evening of 18 August, the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

, which indicated that the High Seas Fleet, minus II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard Sunderland on 19 August, with extensive reconnaissance provided by airships and submarines. The Grand Fleet sailed with 29 dreadnought battleships and 6 battlecruisers. Throughout the next day, Jellicoe and Scheer received conflicting intelligence, with the result that having reached its rendezvous in the North Sea, the Grand Fleet steered north in the erroneous belief that it had entered a minefield before turning south again. Scheer steered south-eastward to pursue a lone British battle squadron sighted by an airship, which was in fact the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a ...

under Commodore Tyrwhitt. Having realised their mistake, the Germans changed course for home. The only contact came in the evening when Tyrwhitt sighted the High Seas Fleet but was unable to achieve an advantageous attack position before dark, and broke off. Both the British and German fleets returned home, with two British cruisers sunk by submarines and a German dreadnought battleship damaged by a torpedo.

The year 1917 saw a continuation of the battlecruiser's routine of exercises and patrols into the North Sea, with few incidents. During this year ''Australia''s activities were limited to training voyages between Rosyth and Scapa Flow and occasional patrols to the north-east of Britain in search of German raiders.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', pp. 279, 281 In May, while preparing the warship for action stations

General quarters, battle stations, or action stations is an announcement made aboard a naval warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the arme ...

, a 12-inch shell became jammed in the shell hoist when its fuze became hooked onto a projection.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 279 After the magazines were evacuated, Lieutenant-Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

F. C. Darley climbed down the hoist and successfully removed the fuze. On 26 June, King George V visited the ship. On 12 December, ''Australia'' was involved in a second collision, this time with the battlecruiser . Following this accident, she underwent three weeks of repairs from December 1917 until January 1918.Roberts, ''Battlecruisers'', p. 123 During the repair period, ''Australia'' became the first RAN ship to launch an aircraft, when a Sopwith Pup

The Sopwith Pup is a British single-seater biplane fighter aircraft built by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It entered service with the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps in the autumn of 1916. With pleasant flying character ...

took off from her quarterdeck on 18 December.ANAM, ''Flying Stations'', p. 8 On 30 December, ''Australia'' shelled a suspected submarine contact, the only time during her deployment with the 2nd BCS that she fired on the enemy.

In February 1918, the call went out for volunteers to participate in a special mission to close the port of Zeebrugge

Zeebrugge (, from: ''Brugge aan zee'' meaning "Bruges at Sea", french: Zeebruges) is a village on the coast of Belgium and a subdivision of Bruges, for which it is the modern port. Zeebrugge serves as both the international port of Bruges-Zee ...

using blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland Harbour in 1914 ...

s.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 51 Although many aboard ''Australia'' volunteered their services in an attempt to escape the drudgery of North Sea patrols, only 11 personnel—10 sailors and an engineering lieutenant—were selected for the raid, which occurred on 23 April.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 281 The lieutenant was posted to the engine room of the requisitioned ferry , and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a high award of a nation.

Examples include:

*Distinguished Service Medal (Australia) (established 1991), awarded to personnel of the Australian Defence Force for distinguished leadership in action

* Distinguishe ...

(DSM) for his efforts.Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 52 The other Australians were assigned to the boiler rooms of the blockship , or as part of a storming party along the mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole", mammals in the family Talpidae, found in Eurasia and North America

* Golden moles, southern African mammals in the family Chrysochloridae, similar to but unrelated to Talpida ...

.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 282 All ten sailors survived—''Australia'' was the only ship to have no casualties from the raid—and three were awarded the DSM, while another three were mentioned in dispatches. One of the sailors was listed in the ballot to receive a Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

, but he did not receive the award.

During 1918, ''Australia'' and the Grand Fleet's other capital ships on occasion escorted convoys travelling between Britain and Norway. The 2nd BCS spent the period from 8 to 21 February covering these convoys in company with battleships and destroyers, and put to sea on 6 March in company with the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron to support minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing control ...

s.Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 303 From 8 March on, the battlecruiser tested the capabilities of aircraft launched from platforms mounted over 'P' and 'Q' turrets. ''Australia'', along with the rest of the Grand Fleet, sortied on the afternoon of 23 March 1918 after radio transmissions had revealed that the High Seas Fleet was at sea after a failed attempt to intercept the regular British convoy to Norway. However, the Germans were too far ahead of the British and escaped without firing a shot. The 2nd BCS sailed again on 25 April to support minelayers, then cover one of the Scandinavian convoys the next day. Following the successful launch of a fully laden Sopwith 1½ Strutter scout plane on 14 May, ''Australia'' started carrying two aircraft—a Strutter for reconnaissance, and a Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the ...

fighter—and operated them until the end of the war. The 2nd BCS again supported minelayers in the North Sea between 25–26 June and 29–30 July. During September and October, ''Australia'' and the 2nd BCS supervised and protected minelaying operations north of Orkney.

War's end

When thearmistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

was signed on 11 November 1918 to end World War I, one of the conditions was that the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...